Command F

During an introductory service design class at Northwestern, a team of designers and I were given the task to design a service that would help students experience belonging in computer science classes. Through the course of ten weeks, our team researched, ideated, and prototyped a service that allowed students in introductory courses to begin building community immediately while becoming more comfortable with CS spaces on campus.

Timeline: Jan-March 2022

Scope: Service Design

Tools: Figma, Google Slides, and Post-Its

Role: design researcher, project manager

Team Members: Orly S. & Lauren L.

Overview

Background: Enrollment in Computer Science (CS) classes is exploding, straining program resources at universities and causing concern among faculty and administrators about how to best respond. While the interest in Computer Science is exciting, large cohorts and classes can make it difficult to feel a sense of belonging, and when students feel out of place, they don’t perform well or persist. Researchers offer at least two reasons for a low sense of belonging:

. It can be difficult to belong if you don’t fit the cultural trope of a computer science major.

The size of lecture classes create additional barriers to forming meaningful relationships among peers, especially during a pandemic when social distancing and mask wearing are enforced.

Problem Statement: How might we create opportunities for students in intro CS courses to casually meet other classmates so they can build their own support system within the CS community?

Solution: a scavenger hunt activity that lets students in intro CS courses meet each other in a fun, NON CS-y way so that they feel a sense of community with their classmates and become more comfortable with CS spaces on campus

Understanding the Problem Space

While we were already given the specific problem our service was meant to tackle, we realized that it was first important to further understand the problem space, especially as a group of all non-CS majors. We each completed two different design research exercises to do so: a mind map and a stakeholder map.

Mindmaps are visual representations of related constructs. Idivided my map into themes, questions, and assumptions I had about the general topic of belonging in CS. This exercise helped me practice purposeful reflection and outline my understanding of our users, related services, and existing insights about the project. It served as a tool of preparation before conducing research with stakeholders.

The stakeholder map served as a diagram of key constituents, their relationship to each other, and the flow of resources between them. In order to create this mind map, I interviewed two CS students to understand the stakeholders they interact with. This map allowed me to identify CS students’ main dependencies and potential opportunities to increase connection around a shared motivation.

Engaging With Stakeholders

Throughout the course of this project, we implemented many different research techniques:

Interviews: we conducted interviews with 10 CS students, 2 non-CS students, 3 CS professors, and 1 PHD student

Service Safari: we explored the resources currently being offered to students

Shadowing: we shadowed CS 111, an introductory CS class at Northwestern

Defining Our Users

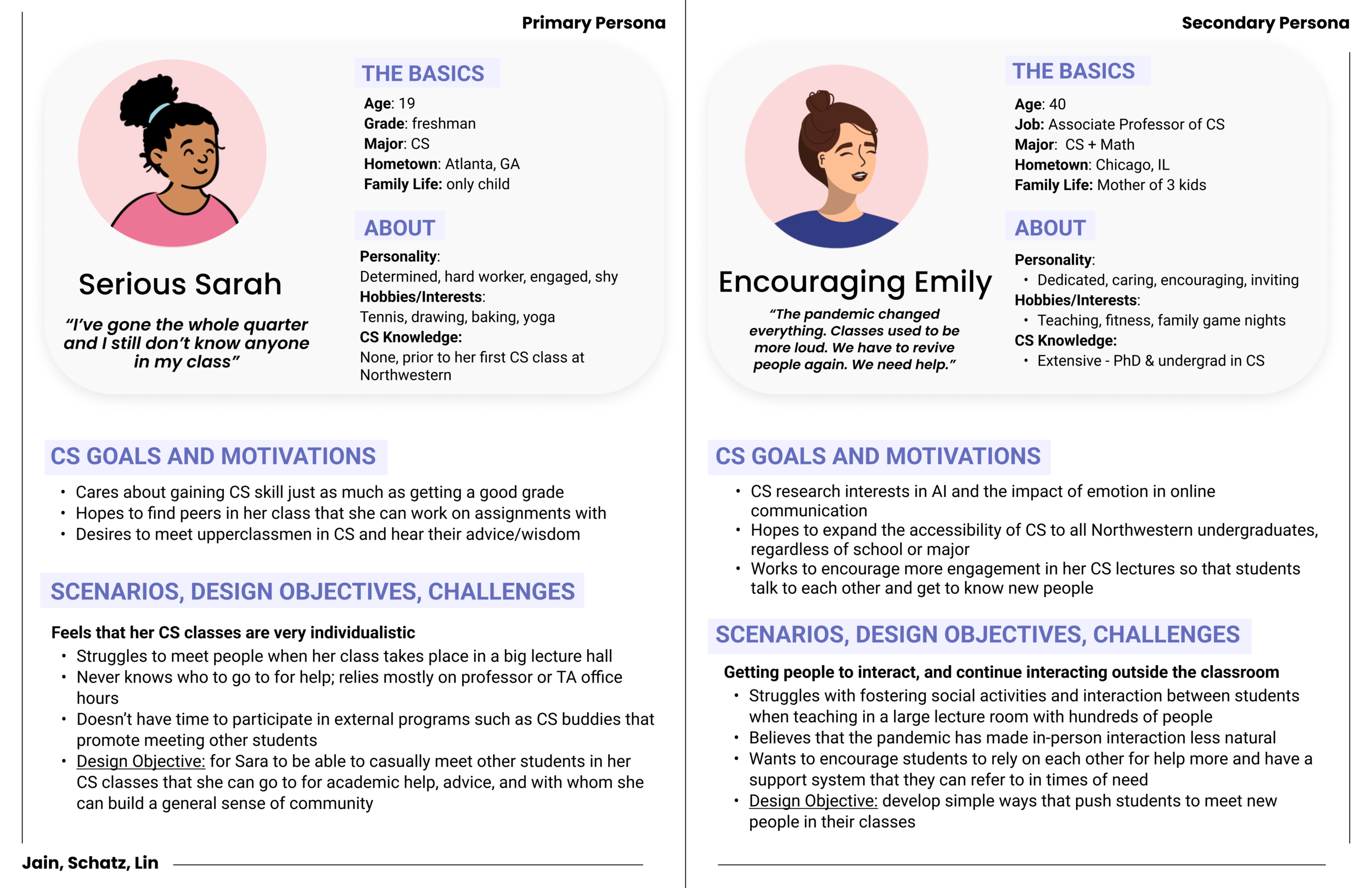

Our initial interviews with students focused on understanding their current experiences in CS. We wished to understand the struggles they faced in CS, the origin of these struggles, and potential areas for growth. We also wanted to understand the general motivations and desires in pursuing CS. These interviews allowed us to narrow down on two more specific personas.

Primary Persona: first-time CS students in introductory classes

Secondary Persona: dedicated professors of introductory CS classes

Synthesizing Our Observations

These personas and interviews allowed us to narrow in on specific themes we wanted to explore further. In order to synthesize our observations, we created synthesis frameworks. These frameworks informed design opportunities, conveyed research methods, and detailed a project plan for the remainder of the quarter. They allowed us to turn observations into surprising insights, identify key discoveries, and develop actionable and meaningful opportunities. In total we created three synthesis frameworks focused on different themes:

Building peer-to-peer connections.

Increasing the visibility and accessibility of resources

Empowering first-time CS students

Ideations

Based on the three synthesis frameworks we created, we generated over 150 ideas aimed at solving the issue. This allowed us to think quickly and pushed us to consider even crazy, bad ideas as well. From these 150 ideas, we settled on 3 to further explore through storyboards. These brought our ideas to life so that we could begin to prototype, test, and validate their worth.

Narrowing In

By testing our story boards on users, we were able to receive much-needed feedback on what concepts could lead to an impact that would directly benefit first-year CS students. The feedback we received is ultimately what made us realize that the most important avenue to target was the connections students are having with other students. Beyond narrowing down our problem scope, we also were able to identify some research insights that guided the development of our final HMW question.

3 Key Research Insights

Our HMW Question

Prototyping Seat Buddies

With our HMW set, we put our first idea into action: Seat Buddies.

Seat Buddies was a service that would assign students in introductory CS classes a partner or small group to sit with during the first few weeks of the quarter. Each class, the partner or group would complete a get-to-know you activity, with the intention that by the end they would have a new friend or familiar face in the class. By giving someone an automatic buddy, we thought this service may reduce the burden of feeling alone. We prototyped and tested three touch points of the service:

the assignment of the seating buddy

the get-to know you activity

physical indicators of grouping in the lecture hall

Pivoting

Overall, we found that the students we tested our prototypes on felt that the connection was forced and unnatural. They didn’t seem enthusiastic about the service, and neither were we. While we thought that our service was addressing a real need of students, it wasn’t getting at the issue in the right way.

Our failure provided a few important insights that we used to guide our future direction:

Students would much rather engage in activities than simply sit next to each other and answer a few cringey icebreaker questions

Students indicated that any engagement needed to occur in a manner that “forced” students to engage with those they didn’t know: there was no incentive for people that already had friends in the class to participate in seating buddies

It was important to keep the service within class time, as we learned that students often didn’t have the time to participate in additional programming, especially if its only purpose was to meet other students

We realized we needed to take a step backward, so we returned to our ideas and began brainstorming again. Our ideas started out bold and broad, but thinking in such a way is what allowed us to ultimately land on a scavenger hunt activity.

Introducing Command F

Rather than utilizing lecture time, which was not conducive to engaging with new people due to the set up of the lecture hall, Command F was a scavenger hunt activity that would take place during the class’ first tutorial session. Tutorials are similar to discussion sections for other college classes and involve 1-12 students and a Peer Mentor (a TA) who helps the students with class material.

This activity made people in tutorial compete against each other in small groups as they completed various missions. These missions were a mix of:

Simply fun activities, such as making tik-toks and taking selfies,

Discussion starters, such as “Who in your group has traveled the farthest North?”

CS-related activities, whether that involved finding a professor’s office, navigating a study space, or decoding a message using binary code

With Command F, we hoped to encourage interaction and engagement in a more active, goal-oriented manner, which we believed would be more successful.

Prototyping Command F

To test out our new idea, we contacted 4 current and past CS 110 students and simulated a tutorial session. I acted as the Peer Mentor, explaining the activity and providing the instructions. Then, we let the four individuals complete the scavenger hunt themselves while one of our designers went undercover to observe the interactions in the group.

The feedback that we got was overwhelmingly positive! All four students thoroughly enjoyed the activity, and our undercover designer noted that the four of them did start to get to know each other over the course of the activity. The interactions felt more tangible and natural than in our Seating Buddies prototype. The students gave us a few important pieces of feedback related to the wording and set-up of the scavenger hunt instructions, but beyond that, Command F had been a success!

At the end of the quarter, we had the opportunity to share our final service design with a group of important stakeholders, including many CS professors and PHD students. To capture our service in a quick and appealing way, we created a short demo video:

Impact

The reaction we got from the professors and PHD students was extremely validating. Many of the professors spoke of trying to initiate similar services as Seating Buddies but failing for the same reasons we did. They understood the struggle to foster engagement in such large lecture halls, especially in a post-pandemic world where interaction like this hasn’t been the norm for years. Importantly for them, they could see how this activity could easily fit into their class structure without causing major problems or work on their end.

While Command F is still a hypothetical service, we believe that there is great opportunity for it to be added to the introductory classes at Northwestern One of the professors asked us to send them our project materials so she could work on implementing it next year!

One of these materials was our service blueprint. This allowed us to visually communicate how customers and service providers interact throughout the service and detailed both the front and back-end processes involved so that anyone would have all the necessary tools and information to put the service into action.

Reflection

What I Would Have Done Differently

-

We were very limited by the length of the class (10 weeks) for this project. Due to the structure of the class, we spent the first 7 weeks in the research and ideation phase and only the last 2 weeks prototyping before our final presentations. This allowed us to prototype two different solutions: seating buddies and Command F, However, with more time we could have prototyped other ideas we had in order to determine which one best solved the needs of CS students. Further testing also would have allowed us to refine our Command F prototype even more.

-

While we were able to talk to 15 students in total and 3 professors for this project, we struggled in recruiting individuals to participate in our testing sessions once we had developed our service prototypes, Being able to test our prototypes on larger groups not only would have simulated a lecture or tutorial session more accurately but also allowed us to get a wider range of opinions that may have validated our prototype and indicated opportunities for refinement.

-

Unfortunately during this project, we only spoke to Peer Mentors a few times. I wish we had been able to further involve them in the testing phase and gotten their opinion on whether Command F seamed feasible and effective to implement in a tutorial session. It’s important to consider all stakeholders involved, including the service providers.

What I Learned

-

Often times when you think about a service, research and efforts are focused entirely on the customer-the person on the receiving end. However, any service must not only have an incentive for the customer but also the provider. If the provider is not happy, this will reflect on the quality of the service and thus the experience the customer ultimately has. As a result, a service designer must consider the views and experiences of all stakeholders involved in the service, no matter what side of it they are on.

-

One of the most vital exercises we did was creating a service blueprint, which allowed us consider every stakeholder, touchpoint, and support process involved in our service. Completing this exercise made me realize that beyond the front-facing process that customers see, so much is happening in the background to make any service possible. It is incredibly important to consider these back-end individuals and processes to determine if a service is feasible to implement and what would be required to do so.

-

After our group prototyped Seating Buddies, we were in a difficult spot. We didn’t like our prototype, and looking back at the other ideas we had at the time, nothing resonated with us. We decided to think big and write down any and everything that entered our mind, no matter how crazy or unrealistic it sounded. One of these ideas was an easter egg hunt around campus, which after some adjustments resulted in Command F. Without our group actively trying to come up with out of the box, “bad” ideas, we never would have landed on our solution.

Closing

Command F was the first service design project I had ever worked on. While learning about new tools such as synthesis frameworks and blueprints, I also was able to compare the design process of a service to that of a product or app. This project made me realize that design is not a linear process. It’s twisted and long and sometimes confusing. Even if we follow all the steps, it’s more than likely you may create something that doesn’t help your users or get at the problem you’re trying to solve. In those moments, however, the most important part is how you react. Even in those times of confusion or failure, a designer is learning what doesn’t work, and that’s almost as powerful as learning what does work. At those junctions, I’ve learned to take every insight I’ve gained and use that knowledge to start front the beginning: to brainstorm, ideate, and prototype again until I land on something that does work. Ultimately, this project reminded me that design is an iterative process, taking time, and repetition, and even failure to get to the solution that matters.